Acute bacterial prostatitis

Acute bacterial prostatitis (ABP) accounts for approximately 5% of cases of prostatitis cases.1 Although rare, ABP requires prompt recognition and treatment as it may result in sepsis. Acute bacterial prostatitis results from proliferation of bacteria within the prostate gland following intraprostatic reflux of urine infected with organisms such as Escherichia coli, Enterococcus and Proteus species.5,6 Men with chronic indwelling catheters, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, or who intermittently perform self-catheterisation, are at higher risk of developing ABP due to their increased risk of bacterial colonisation of the urethra.6,7 There is no evidence that perineal trauma from bicycle or horseback riding, dehydration or sexual abstinence are risk factors for ABP.

The clinical presentation of ABP may be highly variable with symptoms ranging from mild to severe.6 Classic symptoms include:

- fever

- chills

- perineal or lower abdominal pain

- dysuria

- urinary frequency

- urinary urgency

- painful ejaculation

- hematospermia.8

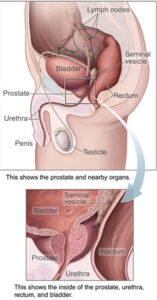

Acute bacterial prostatitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any male presenting with urinary tract symptoms. While gentle palpation of the prostate gland on physical examination will often reveal a pathognomonic finding of an exquisitely tender, boggy prostate gland, care should be taken to avoid vigorous prostate massage as this may precipitate bacteremia and sepsis.9

Acute bacterial prostatitis can be diagnosed clinically, although both urine Gram stain and urine culture are recommended to identify causative organisms and guide treatment. While blood cultures and C-reactive protein may prove useful, a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test is not indicated. Prostate specific antigen elevations are common in the setting of infection and may take up to 1 month postinfection to resolve. Imaging is only indicated when prostatic abscess is suspected in a patient with ABP who is failing to improve with treatment.

Antibiotic therapy for ABP should be based on the acuity of the patient and the known or suspected causative organism. Table 1 outlines the Australian Therapeutic Guidelines current treatment recommendations. While ABP is usually caused by urinary pathogens, sexually transmissible infections such as chlamydia and gonorrhoea should be considered, particularly in young men. If chlamydia is thought to be the causative agent, azithromycin 1 g orally stat or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is appropriate. If gonorrhoea is suspected, ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly and azithromycin 1 g orally is indicated. Contact tracing, notification and treatment is also important in these cases.

In addition to antibiotic therapy, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may offer both analgesia and more rapid healing through liquefaction of prostatic secretions.6

Urine culture 48 hours post-treatment is useful combined with review after 7 days of antibiotic treatment to assess clinical response to treatment.

If the patient fails to improve with antibiotics, a prostatic abscess should be suspected, particularly in men who are immunocompromised, have diabetes mellitus or who have had recent instrumentation of the urinary tract.10 Both computed tomography (CT) and transrectal ultrasound may be used to detect a prostate abscess.11 If perineal puncture of the abscess is planned, ultrasound may guide the procedure.12 However, if surgical debridement of the abscess is planned, a CT scan may be more helpful to define borders of the abscess, plan the surgical approach and to investigate for other abnormalities in the genitourinary system.12

Acute urinary retention may develop as a complication of ABP. Suprapubic tap should be performed to alleviate retention as urethral catheterisation may worsen infection and is contraindicated. In addition to acute urinary retention and prostatic abscess, ABP can lead to sepsis, chronic bacterial prostatitis, fistula formation or spread of infection to the spine or sacroiliac joints.6,13

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

Chronic bacterial prostatitis (CBP) may result from ascending urethral infection, lymphogenous spread of rectal bacteria, hematogenous spread of bacteria from a remote source, undertreated acute bacterial prostatitis or recurrent urinary tract infection with prostatic reflux. Causative agents of CBP are similar to those of ABP include Gram negative rods, fungi, mycobacterium, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Chlamydia trachomatis14 and Trichomonas vaginalis.15 However, Escherichia coli is believed to be the causative organism in 75–80% of CBP cases.14

Recognising CBP can be difficult, as the history and examination are highly variable. All patients note some degree of genitourinary pain or discomfort. Common presentations include recurrent urinary tract infections with no history of bladder instrumentation, dysuria and frequency with no other signs of ABP or new onset sexual dysfunction without other aetiology.16,17

Often the physical examination, including prostate examination, is normal. Prostate examination should be performed to document any abnormalities such as prostatic calculi, which can serve as a reservoir of infection. Prostate stones may be difficult to palpate, but if found, may impact management decisions.

Although the Meares-Stamey four glass test is the gold standard to diagnose CBP, it is rarely used in practice due to time constraints and the difficulty obtaining samples.18 Instead pre- and post-prostatic massage urine samples for analysis and culture may be useful and can guide antibiotic therapy.19 A prostate massage is performed by stroking the prostate with firm pressure from the periphery to the midline on both the right and left sides of the prostate gland. More than 20 leucocytes per high powered field on the post-massage urine sample is diagnostic of CBP.19 If urine cultures show no growth, consider a nucleic acid test for C. trachomatis and culture of prostatic fluid for ureaplasmas. Occasionally, Mycoplasma genitalium is found in prostatic secretions, although its role in prostatitis is unclear. If these tests are also negative, an alternative diagnosis should be considered.

Limited comparative trials exist to guide antibiotic regimens for CBP. Table 1 lists current recommendations. Patients should be warned about the common side effects of extended duration of antibiotic use, such as Achilles tendon rupture with fluoroquinolones.

In addition to antibiotics, NSAIDs may alleviate pain symptoms. Alpha-blockers may diminish urinary obstruction and reduce future occurrences.20 Although less well studied, saw palmetto, quercetin, daily sitz baths, perianal massage and frequent ejaculation may also help to clear prostatic secretions and lessen discomfort. If prostatic stones are present, prostatectomy may eliminate the nidus of infection.